From a waste industry perspective, the long lifetimes of solar PV modules can hinder the economics of setting up recycle and reuse infrastructure, according to an industry veteran. Following on from a feature that questioned the PV industry’s preparedness for the decommissioning phase at the end of project lifetimes, PV Tech Premium spoke to Jan Clyncke, managing director, PV Cycle, a PV-focused producer compliance scheme based in Belgium, to focus on the module recycling and reuse aspect of retiring a solar project.

Clyncke discusses misconceptions about the value of end-of-life materials and the precarious economic viability of reusing panels. This article also covers various countries’ attempts to manoeuvre PV waste streams into effective reuse and recycling processes while even some giant Asian manufacturers shift interest towards take back schemes.

Unlock unlimited access for 12 whole months of distinctive global analysis

Photovoltaics International is now included.

- Regular insight and analysis of the industry’s biggest developments

- In-depth interviews with the industry’s leading figures

- Unlimited digital access to the PV Tech Power journal catalogue

- Unlimited digital access to the Photovoltaics International journal catalogue

- Access to more than 1,000 technical papers

- Discounts on Solar Media’s portfolio of events, in-person and virtual

Or continue reading this article for free

PV panels are “not a great waste proposition”, says Clyncke. This is because optimisation of collection, recycling and decommissioning costs requires knowing when the product will need to be recycled. Unlike smartphones, which have a regular turnover, PV panels are built to last decades, which does not lend itself to investing in building recycling lines and scaling up. Furthermore, decommissioning occurs so far in the future that it’s unclear if the original installers and owners will still exist at that time.

Costing errors

Clyncke claims that decommissioning requirements in the US are inadequate, with the dominant focus still on large commissioning plans, which leads to a lack of accountability at a project’s end-of-life. There is also a common misconception that the value of recovered aluminium frames and other equipment can cover the costs of decommissioning.

Achieving a zero-cost recycling solution for the producer, who must finance the collection and recycling of the PV equipment, is difficult given the additional costs of transport, shipping, overheads and labour. “This is all ignored in some of the decommissioning plans,” claims Clyncke.

In terms of recycling and reuse of modules, Washington State – where there is very little PV installed – is the only US state that has advanced plans for an extended producer responsibility scheme for PV panels. After several postponements, it is due to start in 2027. Several other states have draft bills in place, but Clyncke says a federal law imposed across the US would be a more effective strategy.

In the UK and European Union, on the other hand, PV modules and inverters have come under extended producer responsibility legislation since 2014 as part of the Waste Electronics and Electrical Equipment (WEEE) directive. This requires reporting how much product has been placed into or taken out of the market each quarter as well as what has been treated or recycled.

“It’s not doom and gloom,” adds Clyncke, noting that waste legislation initiated in Europe has started to spread globally where there was none before. Meanwhile, PV Cycle has taken back old panels from Europe, Panama, Senegal and other parts of Africa, while huge Asian manufacturers, including those in China, are contacting the company to process surplus panels.

“It’s not always that waste goes to Africa,” adds Clyncke.

Global decommissioning and recycling efforts

Global movement on this issue can be seen in several countries. In India, solar PV has been put onto and taken off the E-waste laws several times, says Clyncke. Yet, with more than 73GW of PV installed, the subcontinental giant will eventually need to come to terms with this end-of-life phase. Module recycling discussions are being held between the Environment Ministry (MOEFCC) and Ministry of New and Renewable energy (MNRE), partly with EU help.

“A few small-scale private initiatives are also underway to set up recycling facilities but there is no major urgency or fears on this front in India,” says Vinay Rustagi, senior director, global head of renewables, at Indian analyst firm CRISIL.

“As for use of land thereafter, it is a very scarce and precious resource in India. Most likely, it will be used to set up new projects (assuming continued technology viability by then) or repurposed for alternative uses.”

PV Cycle has also been working with Indian authorities to finalise how PV should show up in the waste laws. At present the Indian version of producer responsibility, which uses recycling certificates, puts complete liability on the shoulders of the recycler, an approach that Clyncke criticises.

Japan does not have EPR legislation, but it does have a requirement for large-scale PV plants of >1MW. Owners of such projects must also set aside money in a fund, which is managed by the Ministry of Trade and Industry (MOiT). The requirement is also linked with the Feed-in Tariff (FiT) subsidy, says Clyncke.

There are also discussions in Australia, but they are moving slowly.

“They are realising, ‘Wow, we have 25GW installed, we have to do something about the end-of-life phase,’” says Clyncke. “Maybe not tomorrow, but hopefully within 15-20 years, it will be there.”

Since Brazil has installed 25GW in just five years, Clyncke has also been working with Brazilian authorities trying to convince them about the need for some form of EPR scheme, which can be done in a relatively inexpensive way.

“Brazil is a country like India where everybody thinks waste does not exist because waste always has value,” says Clyncke. “They sometimes scrap the good parts, and the dirty parts end up in the environment. That’s not what we want, of course, as an industry.”

Repower versus decommission

Clyncke expects that in the future large PV power plants will go through 10-year lifecycles with solar cell efficiencies continuing to improve so quickly that repowering will make financial sense and become a standard approach.

“When I started, panels were 180Wp and today you are only in business when you have 400-450Wp for residential rooftops and for the large-scale even 700Wp. So, repowering will stay and become quite important,” he adds.

Journey to reuse standards

Clyncke is also hopeful that any removed panels will be able to be reused. He has worked on this issue since 2021, while attempting to get a standard through at International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) level. A technical report about the reuse of PV panels is now being finalised for publication in Q1 this year. The hope is that the report will convince experts of the need for a technical specification on the reuse of PV panels and then possibly by 2030 to have a global standard in place that can keep players accountable across the globe.

During his waste industry career, Clyncke saw many illegal waste shipments go to Africa, so he is committed to helping avoid that trend with PV modules. Guidance can only go so far as there are also issues with inspection authorities and many loopholes and weak points in the global system that can allow waste to be leaked into illegal environments.

“If you also look to the current situation, it will be really challenging to make reuse economically viable, because the prices of new panels today are so cheap. If you must bring the panels back to a workshop to check and repair them, cost-wise this is suicide, because you will lose money.”

Hazy US recycling plans

Opaque planning can also belie purposeful and optimistic rhetoric around recycling. For example, US asset owners are responsible for removing PV modules at the time of system decommissioning, but only North Carolina’s policy requires recycling or any other specific disposition other than removal from the project site, according to a February 2024 report from the Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI).

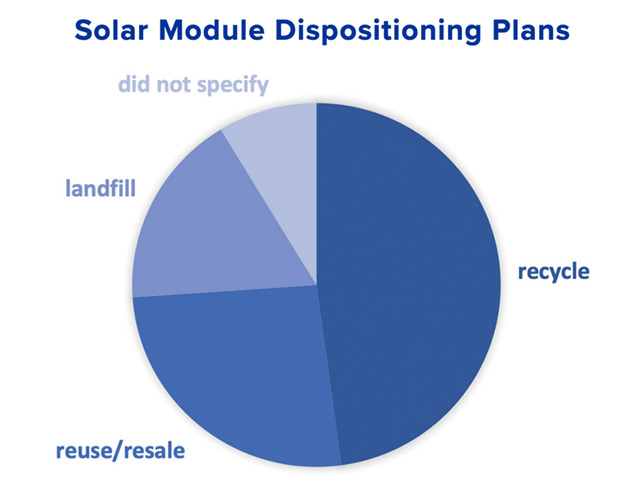

“Some of the plans analysed indicate intentions to recycle PV modules, while others intend to resell modules to recover cost,” said the report authors. “Most of the plans imply that modules that cannot be easily recycled or resold will be disposed of in another manner. Of the 22 decommissioning plans or statements surveyed, only four plans identified specific recyclers or cited a specific recycling plan, while two committed to a zero-landfill policy.”

How well the global PV industry will deal with the explosion of used PV equipment remains unknown at this point, but the two founders of Texas-based PV recycling firm Solarcycle, Suvi Sharma and Jesse Simons, last June also showed optimism when interviewed by PV Tech Premium. Despite, claiming that PV module lifetimes are averaging 15 years instead of 20-30, so significant volumes of end-of-life panels are going to arrive much faster than anticipated, they also showed that recovering almost all of the material in a PV panel is possible in their recycling processes and they believe large-scale illegal dumping of PV equipment can be avoided.