There can be little doubt that the Paris climate deal reached in December was a landmark moment. For 20 years the world had tried to reach an agreement on how best to collectively tackle climate change, but failed. This time around a deal looked more likely, but then only days before the COP21 negotiations got underway the appalling attack on Paris by Islamist extremists threatened to scupper the talks even before they had begun.

Nevertheless, against the odds, on 12 December 2015 world leaders defied history and the more immediate peril from terrorists to reach a deal. That deal leaves a lot still to resolve, and critics have been quick to condemn it for its lack of the necessary detail or teeth to drive forward the energy transition. But the very fact a deal has been reached is a huge statement of intent by the world finally to get to grips with arguably mankind’s biggest existential threat.

Unlock unlimited access for 12 whole months of distinctive global analysis

Photovoltaics International is now included.

- Regular insight and analysis of the industry’s biggest developments

- In-depth interviews with the industry’s leading figures

- Unlimited digital access to the PV Tech Power journal catalogue

- Unlimited digital access to the Photovoltaics International journal catalogue

- Access to more than 1,000 technical papers

- Discounts on Solar Media’s portfolio of events, in-person and virtual

Or continue reading this article for free

“It’s changed from ‘if’ to ‘when’,” says Sean kidney, chief executive of the Climate Bonds Initiative. “It’s a clear message to the world that this transition is happening. Yes the detail is still a bit fudgy but when you get 187 nations putting forward climate change plans, that’s pretty damn amazing.”

For those working in the solar industry the Paris deal is of particular significance. Since the 2009 Copenhagen climate summit, when high hopes of a deal fizzled out, solar has been arguably the star performer among the clean energy technologies that will help wean the world off its fossil fuel habit. Indeed many ascribe the fact that a deal was reached in Paris at all to the progress that solar and wind power have made since Copenhagen. As governments around the world now retreat to their respective corners to work out how to deliver on the pledges made in Paris, solar is expected to be central to most countries’ and regions’ plans.

“It’s now almost universally recognised that solar will be a principal contributor to addressing climate change,” says John Smirnow, secretary-general of the newly formed Global Solar Council. “I don’t think there’s any doubt about that.”

But while having an agreement is one thing, delivering it is another altogether. Some have likened the progress made by clean energy in the past five years to a juggernaut slowly gathering momentum. While that may be true, another equally apposite analogy would be that of the oil tanker, for which a change of direction is a protracted and tortuous business. Apply that to the current energy paradigm, and it’s clear that even in the context of the incredible advances made by solar and its kin in the field of renewables, there is still a long way to go. Policy, regulation, the prevailing flow of investment into the energy sector … these are all still largely geared towards the incumbent fossil fuel-based energy system whose days must be numbered if the world is to achieve its aims. In other words, this is still a marathon for solar, not a sprint.

“Paris gives us a framework to move forward but the immediate impact on the solar industry is not going to be noticed for some time,” says Michael Taylor, senior analyst at the International Renewable Energy Agency’s Innovation and Technology Centre in Bonn, Germany. “Like all things, there is an element of inertia in moving from agreements to implementation. It will take some time for the coordination of additional policies to come through.”

Nevertheless, the scale of the opportunity for solar is enormous. To paraphrase Sean Kidney, it’s now a question of when rather than if the clean energy transition will happen. This article explores some of key building blocks that are now being put in place to ensure PV can make the most of the big opportunity it has post-Paris to become one of the world’s main energy sources.

Finance

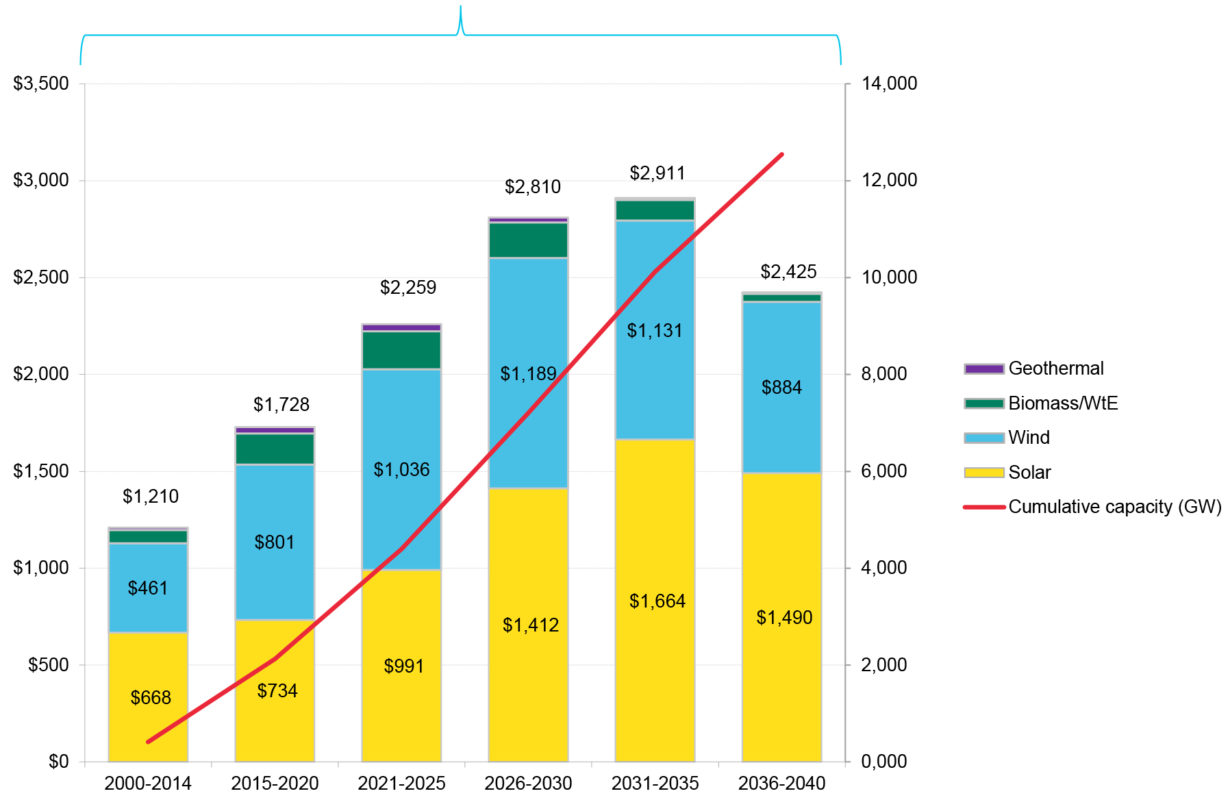

How the energy transition will be financed is the US$12 trillion question. That at least was the investment figure for keeping global warming under 2 degrees Celsius cited in a January report, “Mapping the Gap: The Road from Paris”, by Bloomberg New Energy Finance and the sustainability body Ceres. That’s some US$5 trillion more than under the ‘business as usual’ scenario outlined in the study. Within the report’s projections, solar would take a significant share of this investment, particularly in the 2030-35 period when it would attract US$1.6 trillion (see graph, above).

These are all massive, almost incomprehensible sums. Yet, the question of whether that money will be found is less one of whether it exists than whether it can be directed to the right place. The global financial markets could fund the energy transition several times over and still have plenty to spare. The issue is that at the moment the capital needed to deploy solar and other clean energy technologies at the sort of scale required is still flowing largely in the wrong direction – into fossil fuels.

“The money goes where the returns are,” says Alex Perera, head of the renewable energy programme at the World Resources Institute in Washington. “It’s not like you’re trying to convince bankers to put money in different things; they don’t really care what they’re financing. It’s all about the risk-return profile. So it’s really about how you de-risk the good stuff and improve the returns of the good stuff, and then how do you add risk to the bad stuff.”

With that in mind, one of the big efforts currently going on to turn around the oil tanker of the world financial markets is to highlight to the investment community just how risky their investments in coal, oil and gas are. At the forefront of that is London-based think-tank, the Carbon Tracker Initiative, which is building up a body of evidence to demonstrate this point.

Speaking at a recent solar finance event in London organised by PV Tech Power publisher Solar Media, the organisation’s CEO Anthony Hobley said its latest analysis suggested that some US$2 trillion of planned fossil fuel projects “do not make financial or climate sense”. The kind of projects Hobley referred to are the currently marginal ones in locations such as the Arctic or tar sands, where extraction is risky, costly and dirty.

“If those projects go ahead, there’s a very high likelihood that US$2 trillion will be wasted,” Hobley said. “It will create stranded assets in the energy sector. And if all the money is poured into those projects and wasted, the global economy still has to find that money again to fund the clean energy alternatives.”

Hobley said the relevance of this work to the solar industry was to prevent money being spent by the fossil fuel industry that the renewable energy industry could spend more effectively: “Our work is to ensure the financial markets truly understand the risks, so fossil fuel pays the true cost of capital and you guys [the solar industry] are competing on a level playing field.”

Hobley said that the trend of fossil fuel divestment was now picking up pace and reaching meaningful levels. The next part of that story would be the extent to which the solar and other renewable energy industries can offer investors an alternative place to put their money. Many mainstream institutional investors such as pension funds would find it very difficult to divest unless they had a clear choice of where to put their money, he said.

“What those who’ve committed to divest-invest need is the second part of that,” Hobley said. “What do they do with the money they’re divesting from fossil fuels but still want some exposure to energy? There’s a huge opportunity for [the solar industry] to help them. Obviously some work needs to be done to create the right type of products and investment opportunities for them. But they’re very eager to do that now because they’ve committed to it.”

Creating those alternative investment opportunities will indeed be the big task for the solar industry now if it wants to soak up some of the capital being divested from fossil fuels. As such there will be no single answer to how it does this, but according to Kidney there are some tantalising signs of how the necessary volumes of capital may start to flow into renewables, from green bond issues to high-level groups starting to look seriously at the question.

For example, Kidneys says, India’s Securities Commission has just put out green bond regulations, citing the country’s intended nationally determined contribution (INDC) – the pledge it made in Paris to curb emissions. “This is not an environment ministry or renewable energy ministry it’s the securities regulator,” Kidney says. “That’s the sort of change we are seeing now.”

Meanwhile, former New York mayor Michael Bloomberg has been appointed to chair an international task force to examine the financial exposure of the companies to the risk of climate change. “Central bankers, these are the grey men of the grey men and they have a group looking at sustainability issues and climate change headed by Bloomberg. That’s kind of new!” Kidney says.

Policy and regulation

Globally, Kidney says he expects investment in solar and other renewables to grow significantly in the coming years. How that pans out regionally or at an individual country level, though, is another matter as “perverse policy situations” around the globe create a somewhat uneven regulatory landscape for investors and developers to navigate, Kidney adds.

As such this is another of the big-picture issues for industry and policy makers to address to ensure solar plays its full part in the energy transition. The main policy drivers for delivering the Paris vision will be the INDCs that countries committed themselves to ahead of the talks (see box). Aside from these, a number of solar-specific initiatives have also recently launched to address the policy and regulation questions.

The Terrawatt Initiative, for example, was launched on the fringes of the COP talks in December. Instigated by heavyweight French independent power producer, Engie, the venture describes itself as a private sector-led non-profit body aiming to mobilise investment in one terawatt of additional solar by 2030. Speaking to PV Tech Power, its secretary-general, Jean-Pascal Pham-Ba, explains how solar’s shift to greater scale is currently being hampered by the patchwork of market rules in force around the world.

“The fact that each and every country has its own regulation, its own way to do things, makes solar development not scalable,” he says. “You have to start from fresh each time, and each time you have to pay a lot for studies and advisory fees to have a sense of what’s going on, whereas the resource is very well known and the technology is very well known; the regulatory framework is the hurdle, and it means developers can’t industrialise the development process.”

Pham-Ba says the Terrawatt Initiative’s main aim is to work with stakeholders around the world – drawn from industry, finance, global bodies such as IRENA, utility companies and so on – to work out how to “streamline” the solar value chain globally.

This endeavour will focus on a number of priority areas, such as drawing together best practice from around the world on solar market regulation and contractual arrangements. “That’s something we’re going to work with IRENA on in the coming months, so we can offer a set of standardised master agreements, which will be considered as bankable by themselves, without having to spend hundreds of thousands of euros in legal fees each time you do a 10MW project,” Pham-Ba explains.

Another aim will be to develop new business models that aggregate, package and de-risk the many small individual solar assets being built around the world and offer them to market at the sort of scale that would make them interesting to institutional investors. One idea is to create a new investment “label” for solar assets, says Pham-Ba.

“This would be very important to secure the safety and security of the market,” he explains. “The last thing we want is that this sub-prime type stuff happens [with solar], which would be a catastrophe financially but also an environmental catastrophe, because there will be a bigger distrust after that of solar and the whole value chain, which means we won’t be able to reach the transition.”

IRENA’s Michael Taylor says there’s no “silver bullet” in terms of drawing up universal policy and regulation for a global solar market but agrees there is much that countries can learn from each other. “Countries still have to develop their own internal capacity and institutional arrangements,” he says. “As we have seen in countries like South Africa, Brazil, Chile and Jordan once that has bedded in, there has been a rapid scaling up of deployment. There are lessons we think can be shared between countries that will help them enjoy a smooth acceleration.”

Governance and lobbying

One area where the global solar industry is almost certainly going to need to raise its game in the coming years is in the area of lobbying. According to Hobley, although the fossil fuel appears to be in “structural decline”, it is unlikely to go without a fight, making it a potentially dangerous opponent to a relatively new industry like solar.

“The fossil fuel industry still has a lot of money, it still has a lot of political connections and they know how to influence governments,” he said. “And if you don’t think they aren’t going to lobby like hell to slow you down then I think there’s a certain naïvety. So you need to ensure your trade associations are properly funded to compete with their trade associations, that your lobbyists are sat in the same dinners, in the same behind-closed-door conversations.”

In building its capacity to take on the fossil fuel industry at its own well-practised game, two recent developments will likely further solar’s cause. One is the International Solar Alliance, instigated by Indian prime minister Narendra Modi, the other the long-awaited Global Solar Council. Like the Terrawatt Initiative, both were launched on the sidelines of COP21 in December.

The Global Solar Council will bring together the world’s solar industry under one umbrella, for the first time giving the industry representation at an international level. Its main purpose will be to function as a high-level lobbying organisation, working with governments, multilateral bodies such IRENA, the International Energy Agency and G7’s Clean Energy Ministerial to represent solar’s interests at the policy level.

According to its secretary-general John Smirnow, formerly of the US Solar Energy Industry Association, aside from lobbying, the organisation also sees itself as having a key role to play in building capacity among new or emerging solar markets.

“For countries that haven’t yet fully engaged in solar, there’s going to be a huge need for local capacity building, whether that’s technical expertise or building relationships with local energy providers and local government,” Smirnow says. “And that’s going to be an important focus for the council: to utilise our network of technical expertise to help build solar capacity at the local level.”

Already the council represents more than 50 national solar associations, Smirnow says, a number he hopes to grow this year. “As associations we want to help each other grow and share the knowledge, the technical expertise, the lessons learned from some of the more established associations with some of the new, younger associations and help grow associations that don’t even exist today,” he says.

The right direction of travel

In the context of the ambitions set out in Paris and the hopes many have for solar’s part in delivering that vision, there is much work to be done, and the road will be a long one. As IRENA’s Michael Taylor points out, there is no “easy fix” for accelerating new market opportunities for solar. “There are a lot of dominoes that need to be lined up before we can see that happen,” he says.

But only a month or two after the Paris deal was reached, even though that deal itself lacked any significant teeth, there is plenty of evidence to be found of the catalytic effect many had predicted a positive agreement would have. Particularly encouraging is the extent to which there appears to be new momentum within the solar industry to operate collaboratively, something that has hitherto not been one of its strengths and put it a significant disadvantaged to the well-funded, well-connected fossil fuel business.

It is far too early to gauge the extent to which solar will capitalise on the momentum from Paris, but for now the signs are promising.

As Carbon Tracker’s Anthony Hobley puts it: “The way I think about it is very simple: a huge flashing neon sign that says ‘Direction of travel this way’. There’s no question that we’re in the middle of a technological transition and what the direction of travel is. The only question is will it be fast enough to stabilise the climate at 2 degrees?”

This article is the cover feature from the latest edition of PV Tech Power. To read the issue in full, click here.

Driving the energy transition

In the run-up to COP21, nations were required to set out their emissions reduction pledges in so-called intended nationally determined contributions (INDCs). These will be the starting point for policies countries now implement to meet the goal of the Paris agreement. We’ve selected some promising solar markets and summarised briefly any good omens for future solar deployment be it through an emissions pledge, renewable energy goal or a specific solar target.

India 40% of installed electric power capacity to come from non-fossil fuel sources by 2030, along with a 33-35% reduction in the carbon intensity of its GDP from 2005 levels; a five-fold increase in renewable energy capacity to 175GW by 2022, including 100GW of solar.

Egypt Will refocus energy subsidies from fossil fuels to renewables, replace “obsolete” generation assets. Praises renewables ability to help it meet its economic targets as well.

Saudi Arabia Will implement “ambitious programmes” to increase renewable energy’s contribution to the energy mix”; scope to include PV, solar thermal, wind and geothermal energy, and waste to energy systems. A competitive procurement process for renewable energy is said to be under preparation.

Iran 4% reduction by 2030 compared to 2010 with GCCT, nuclear and renewables

Tunisia Country will reduce carbon intensity by 41% by 2030.

Morocco 32% reduction by 2030, targeting 14% of its power from solar by 2020.

Algeria Emissions reduction of 7-22% by 2030 (7% by own means, 22% with finance and technology help). Algeria’s INDC notes the country has one of the best solar resources in the world putting the annual figure at five billion GWh.

European Union At least 40% reduction in emissions by 2030 with member states determining how they do so. There are no replacement country-level renewable energy targets to follow on from the 2020 goals, yet.

Russia 25-30% reduction on 1990 by 2030; makes one reference to increasing the share of renewables.

Turkey Up to 21% emissions reduction with solar to reach 10GW by 2030.

Kenya 30% emissions reduction 2030 compared to business as usual with geothermal, solar and wind energy listed as a focus for efforts.

Nigeria Specific target of 13GW of PV by 2030.

South Africa Will peak emissions in 2020; lists solar as a key technology.

USA Pledge to reduce emissions 26-28% by 2025 compared to 2005 levels with “best efforts” to reduce by 28%; cites Clean Air Act and other existing policies.

Canada 30% emissions reduction by 2030 compared to 2005, very little detail on how. New government could be more bullish on renewables.

Brazil 45% renewables by 2030 with 23% renewable minus hydro by 2030 through wind, solar and biomass.

Mexico 30% emission reduction by 2020, 50% by 2050; will promote investment in solar for high irradiation areas and also will promote DG rooftop solar.

China 100GW of solar by 2020 with current installed capacity listed as 28.5GW, not including 2015 deployment.

Japan Emission reductions of 26% by 2030 compared to 2013; 2030 target for 7% of electricity to come from solar.

Republic of Korea 37% GHG reduction from current policies.

Indonesia 29% GHG reduction by 2030 and 23% renewable target for 2025.